BY CHRIS SAUNDERS

Gray clouds hang above peaceful, tree-lined Mascoma Lake on a June morning. Just off the water, Howard Shaffer’s New Hampshire living room resembles a makeshift classroom for Nuclear 101. A coffee table holds stacks of 15 to 20 books articulating the attributes of nuclear power.

Behind the table, a 7-foot-high poster leans against the wall. Three highlighted statistics about the worldwide nuclear market dominate: 32 Countries with Nuclear Programs; 93 Reactors Being Built; 439 Reactors in Operation.

In a chair rests a framed picture of the USS Seawolf, the second U.S.-built nuclear submarine on which Shaffer served while in the U.S. Navy. Tucked in the frame’s lower left corner, a wallet-sized black-and-white photograph taken in 1964 shows a proud Howard in his officer’s best next to his bride, Mariann, in her white satin wedding dress.

Shaffer sees nuclear power as part of the solution for U.S. energy needs. And education is his answer to achieve that solution.

“I’ve always tried to make it educational, but I’ve come to the conclusion that there’s a small group of people who have had an emotional reaction,” Shaffer said specifically about the fight to close Vermont Yankee, a nuclear power plant in Vernon, Vt. “You could almost classify it as a collision of two worlds, two different points of view. One’s what science says and looking at risks and benefits and numbers, and the other is looking at it in absolutes.”

A nuclear engineer for 35 years, Shaffer classifies himself as a consultant and citizen activist. His business card reads “Nuclear Public Outreach.” The signs and books are among the tools he brings to public meetings as a proponent of nuclear power.

Relying on his industry expertise and education, he sees his role as an educator, attempting to reach the public to debunk the myths that, he says, come from anti-nuke activists playing on public fear.

Voices like Shaffer’s can be heard more regularly today as advocates of nuclear energy have gained momentum with the Bush and Obama administrations. Both have reached for nuclear as a possible answer for the country’s energy woes, launching what some have dubbed a “nuclear renaissance.”

Congress has followed the lead, first with the Energy Policy Act of 2005 that established loan guarantees for nuclear expansion. The American Power Act, authored by Sens. John Kerry and Joe Lieberman and awaiting its fate, would set aside $54 billion in loan guarantees for nuclear power.

And in summer 2010, the Department of Energy committed $18.2 million in grants to colleges and universities around the U.S. aimed at nuclear education for the next generation.

The South will see the first two nuclear reactors to be built in the U.S. in 30 years, near Augusta, Ga. They will cost more almost double that of early-generation reactors.

And those could be the first of many: as of June 2010, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) reports it is reviewing 17 applications for construction and operation on a total of 26 new reactors.

Nuclear power has an almost 50-year operational history in generating electricity in the U.S. But proponents, whom Shaffer would call the scientists, and opponents, whom he would call the absolutists, have raised a powerful chorus on the cusp of renewed nuclear investment.

They have their answers, too. Despite the high initial costs, proponents tout the need for more power generation to meet U.S. demand. Opponents say, however, that the “nuclear renaissance” would be more of a failed regurgitation than a flourishing enlightenment.

OBAMA’S NUCLEAR BULLS-EYE: PLANT VOGTLE

Mike McCracken’s middle-age handsomeness makes him more look like a pro-golfer who would be at home on Augusta’s links 25 miles north of where he works at Plant Vogtle in Burke County, Ga., a community of almost 23,000 residents.

As the spokesman for Southern Nuclear, the company that operates the plant, McCracken is just as much everyman as he is scientist. He mixes casual chit-chat with his technical nuclear jargon. He asks a visiting reporter if the Atlanta Braves’ most recent phenom, Jason Heyward, can play that well all season. He mentions how a photojournalist shooting the Plant Vogtle’s water tower looks like another Atlanta Brave, Chipper Jones.

With his affable dialogue, he’ll also give you his answer. Hard hat and Smith and Wesson safety goggles framing his close shave and ready-for-camera hair, he points to part of the solution, an excavated site where the two new nuclear reactors will rise at Plant Vogtle.

The future site of Unit 3 at Plant Vogtle in Burke County, Ga., is excavated and 95 feet deep. It will be the foundation for a new reactor and control room. Photo by Lauren Frohne

With pride he notes that within seven years, Vogtle will be the first—and only—nuclear plant in the U.S. with four reactors.

He’s proud that Southern Nuclear has broken ground on the reactors in anticipation of receiving a full operating license.

And he’s proud that the plant was hand-picked by the Obama administration to carry the flag for a nuclear renaissance.

In many ways, Vogtle was an ideal choice. Because it was poised to start construction even before it received the federal loan guarantees, federal officials saw the site as a place where the loan guarantees would find little controversy.

The plant also has a very clean safety record. Outside of a brief power loss in 1990, Vogtle’s record with NRC holds no penalties.

McCracken, a former high school science teacher, said that he aims his education and public outreach at middle- and high-school students in the area, elected officials and key leaders in the community. He added that once a year the plant sends out a safety brochure and calendar to every resident within a 10-mile radius of the plant, and sirens undergo a yearly test for emergency preparedness.

But the passing safety grades from the NRC and the emergency plan do not assuage the fears of a small, poor community in immediate proximity to the plant. The almost 2,000 residents of Shell Bluff, a rural community based on farming and all-the-church-you-can-fit-in, stare at a multitude of signs warning against trespassing on the red-clay land on which they used to roam free.

“You used to be able to go out to the river and fish anytime you wanted to, and you wouldn’t worry as far as any radiation or anything in the fish,” said Claude Howard, a Shell Bluff resident who can see the water vapor from the plant’s two cooling towers from his porch 10 miles away. “But once Plant Vogtle came into the neighborhood, into Burke County, things really changed. …(T)hey post no trespass signs, and they have a tendency to push people away and push them outside the block.”

Historically an agricultural community, Burke County now prominently features Plant Vogtle’s two cooling towers. By 2017, four cooling towers will be seen on the horizon. Photo by Lauren Frohne

Vogtle officials such as McCracken see the signs as one of many security measures emphasized more heavily at U.S. nuclear plants after Sept. 11, 2001. Residents say the signs and the emergency tests lead to uncertainty and fear.

“Last Thursday, I was down one of the roads, and an older lady was out when the alarm went off,” said Annie Laura Stephens, a vocal Shell Bluff community leader. “She was sitting out in her yard and said she had her bags packed, and she didn’t know whether they were going to come and get her or not.”

Anti-nuclear activists fighting the construction of the two new reactors have seized upon safety issues that build on residents’ fears and anxiety. In particular, activists have chosen dry cask storage as a point to object to any expansion.

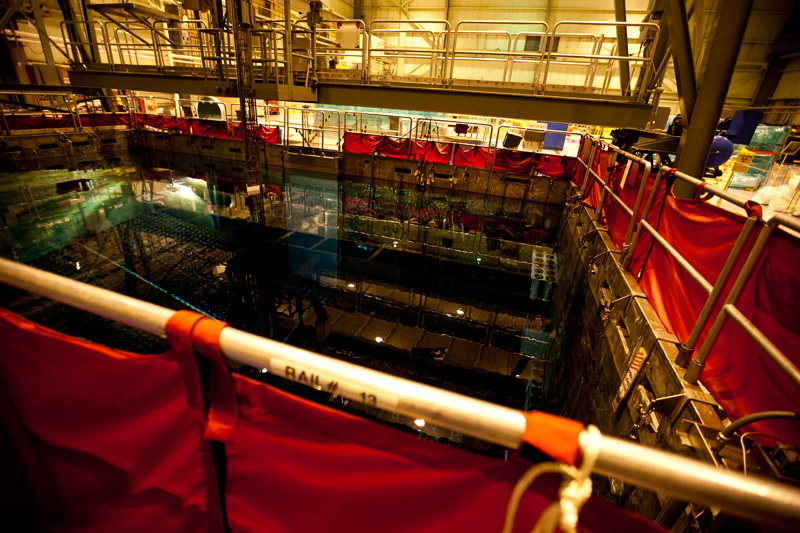

Plants around the U.S. have used on-site cooling pools to store decades-worth of rods, which hold the spent fuel, the radioactive waste from the reactors. Many of these pools have reached or are reaching their capacity, a problem that would have been remedied by the proposed storage at Yucca Mountain. But the Obama administration axed the Nevada location as an option.

Spent fuel pools are used in nuclear plants to store radioactive waste. Vermont Yankee, photographed here, uses one pool that is four stories deep. It holds nearly all of the plant’s spent fuel from the past 38 years. Photo by Lauren Frohne

The NRC reports that since 2002, U.S. nuclear power plants’ storage of spent nuclear fuel has increased by 30 percent, from 46,000 to 60,000 metric tons. That increase totals almost 31 million pounds of spent fuel.

As spent-fuel pools fill, plants have begun storing the rods in giant steel cylinders surrounded by concrete, a process known as dry cask storage. There are 54 licensed Independent Spent Fuel Storage Installations in the U.S.

Plant Vogtle has used two spent-fuel pools to store its rods, but the plant estimates that dry cask storage will be needed on-site by 2014. The 14-foot tall cylinders that Vogtle will install can each hold up to 32 spent fuel assemblies, each one consisting of a bundle of rods.

In an attempt to point to safety issues, in November 2008, a group filed a petition contending that Plant Vogtle’s application for a construction and operation license for the two new units did not contain any plans for its storage of low level radioactive waste. But the Atomic Safety and Licensing Board’s three-member panel determined in May 2010 that an omission of such information did not create a legal deficiency.

To complicate concerns about safety and environmental hazards, across the Savannah River from Plant Vogtle sits Savannah River Site (SRS), a Department of Energy facility once used in the production of nuclear weapons. For years, Shell Bluff residents have had concerns about the safety of that plant, particularly in light of a study released in October 2008 about the health of SRS workers compared with the general population.

According to a National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health study, though SRS workers had lower death rates than the general U.S. population, more male workers died from pleural cancer and leukemia than men in the general U.S. population. The study findings also showed that workers faced a higher risk of terminal leukemia as recorded radiation doses increased.

Some plants house the spent fuel on their site in dry casks above ground. The one shown here at Vermont Yankee stores the waste in rods placed in these cylinders on an air-cooled platform. Photo by Lauren Frohne

Louis Zeller, the science director of the Blue Ridge Environmental Defense League, has acted with other groups to file legal challenges with the NRC against Plant Vogtle’s expansion. He said studies that try to establish a connection between high cancer rates and nuclear plants are emblematic of his concerns over the long-term damage done to a nuclear community, such as Shell Bluff.

“Even though there’s been no big accident, no meltdown (at Plant Vogtle), things still aren’t safe,” he said. “It’s a constant drip, drip, drip of these radioactive pollutants.”

Though studies have not made a direct correlation between health declines and Plant Vogtle, residents in the Shell Bluff community do not make a distinction. Charles Utley, a Georgia minister who has spent his entire life in the area and who commutes between Augusta and his Burke County roots, said that he doesn’t need studies to validate what he sees in the community as he visits relatives.

“I don’t see anything in the air,” Utley said. “But if you live there long enough, you’ll know the effects of it.

“All I’m saying is that had the people had the knowledge they have now, a lot of decisions would have been made. I wouldn’t see the number of cancer-related deaths. I wouldn’t see the high rate of stillborns, children born with tumors.

“Nobody has to tell me about them. I know them for a fact.”

SAFETY ISSUES IN VERMONT

Nobody has to tell Vernon, Vt., a bucolic countryside community of no more than 2,100 residents, about the safety and environmental concerns that accompany a nuclear power plant. The town has lived in the shadow of a series of Vermont Yankee mishaps that date back eight years. Then Entergy, a Louisiana-based energy company, bought the plant for $180 million from Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Group, made up of 12 New England utilities.

A plumber by day, Bob Bady lives in Brattleboro, Vt., 10 minutes from the plant. His house is hidden at the end of a gravel road deep in Vermont’s green landscape. His long hair suggests a hippified, casual approach to life. But he is anything but passive as he rattles off Vermont Yankee’s safety breaches like he would a list of his top-5 least favorite movies.

“If you look at the long list of mishaps and problems they’ve had over the last several years,” Bady said, “then you’re basically looking at a company that (has) cooling towers that collapse, leaks of thousands of gallons of tritium into the groundwater around the plant (and) into the soil around the plant, fires and circulator valves that don’t work.”

Like Howard Shaffer’s answer, Bady’s also lies in education, but in a different way. With civil disobedience, he works to educate other citizens about what Vermont Yankee’s thumbprint has done in southeastern Vermont.

In January 2010, he and other members of a citizens’ group, Safe and Green, organized the Step Up to Shut It Down March. They trekked 126 miles from Brattleboro to Montpelier, the state’s capital. They held a news conference at the capitol to present lawmakers with a petition signed by 1,600 citizens who wanted the plant closed.

Married to the mishaps at Vermont Yankee is the issue of the plant’s power uprate. Plants are approved for a certain operating capacity, but owners can request a higher rate to generate more power. Entergy submitted a request in 2003 to run Vermont Yankee at 20 percent more than its capacity. The NRC gave its OK in 2006.

According to the NRC’s numbers, the agency has approved 129 uprates at U.S. nuclear power plants. Nuclear proponent Shaffer said that a plant can withstand this increase because some plants were essentially designed for such a boost.

“As time has gone by, knowledge has improved, particularly computer power and experience with plants in how to do analysis,” Shaffer said. “Because of the limitations of knowledge in the ’60s, engineers put in more fat. So it was determined that it was safe to boost the power of these plants, and depending on the plant’s design and original licensing, some plants could go more than others.”

All the points on safety and operating capacity have taken on new life because Vermont Yankee is up for relicensure. With its questionable track record and uprate, the plant faces an uphill battle in obtaining relicensing by March 2012.

While the NRC generally holds that responsibility, Vermont has found a way to supersede the regulatory agency’s decision. In May 2006, the Vermont legislature passed Act 160, which gave licensing power to the elected officials of the state, not the NRC.

Vermont is the only state in the U.S. that holds this executive power. In February 2010, the state senate voted 26-4 against relicensing, a vote that could change if November elections bring in new state leaders. They could reverse the earlier vote before the 2012 deadline.

Failure to relicense Vermont Yankee could crimp the national push for a nuclear renaissance, which depends more on relicensing and extending the life of current nuclear plants rather than building new ones. Fourteen plants, including Vermont Yankee, have applications for relicensing under review. Plants that are not relicensed are decommissioned or taken out of service, a process that can take years as other power generation takes over and plants slowly shut down.

THE BILLION-DOLLAR QUESTION

A large black super-computer with red and green gauges and other hardware encased by metal and glass looked like mocked-up “Star Trek” set behind President Obama. He had come to the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) Local 26 in Lanham, Md., to signal the Department of Energy’s renewed investment in nuclear power. That February 2010, Obama announced the first loan guarantees to break ground on the construction of the first two nuclear reactors in the U.S. in almost three decades.

Plant Vogtle’s twin cooling towers stand on Southern Company’s 3,000 acres of land in Burke County, Ga. In the foreground, land has been cleared for the construction of Vogtle’s two new reactors and cooling towers. The nuclear industry boasts the construction as the beginning of a “nuclear renaissance.” Photo by Lauren Frohne

“And this is only the beginning,” Obama said. “My budget proposes tripling the loan guarantees we provide to help finance safe, clean nuclear facilities.”

Obama handed out the loan guarantees that had been made possible through the Energy Policy Act of 2005, which President Bush signed into law in August 2005. It addressed the cost of U.S. nuclear power, which has faced opposition because of high-stakes investments needed up front.

The first of those loan guarantees went to Burke County, Ga., where Obama committed the $8.3 billion for the first nuclear construction since 1977.

Plant Vogtle’s reactors stand on 3,100 acres that flank the Savannah River against a rural eastern Georgia backdrop. In 1974, construction began on the two initial reactors, Unit 1 and Unit 2, that along with another nuclear plant in southeastern Georgia generate a little more than one-fourth of the state’s electricity.

Unit 1 came on line in June 1987, Unit 2 in May 1989. But they did so at a cost. The U.S. Energy Information Administration reports that during the reactors’ construction, Vogtle’s increased to 13 times the original estimated cost, from $660 million to $8.87 billion.

That means that Obama’s loan guarantees would not have even covered the final cost of the first two reactors. And his recently allocated $8.3 billion will cover slightly more than half the $14 billion projected for the two new reactors.

McCracken, spokesman for Southern Nuclear Public Affairs, says he anticipates the NRC will award a Combined Construction and Operating License, the last hurdle for Vogtle’s expansion, in late 2011 or early 2012. Plans have Unit 3 coming on line in 2016 and Unit 4 in 2017. Coal will provide most of Georgia’s power—it already accounts for two-thirds—until at least 2020.

With fluctuating costs and an uncertain future in nuclear markets, the question of government investment arises, especially at Vogtle. But what the government’s guarantees signal is just a starter solution. Eventually private investors will have to fill the bill if more reactors, more plants and more nuclear construction are to continue.

THE GOLD RUSH

The multimillion-dollar lifeline of more nuclear investment is attached to the citizens of Burke County, the people of Vernon, Vt., and all those living in and around the 65 nuclear power communities in the U.S.

Plant Vogtle has worked its nuclear magic with an economic promise to those living in what used to be a predominantly agricultural economy. It created 900 new jobs to build Units 1 and 2. Units 3 and 4 when operational could bring 800 additional jobs just at the plant. Add to that the 3,000-plus jobs Shaw Group, the contractor on the project, estimates construction will bring to Burke County over the next seven years.

The jobs carrot is a mirage to some Shell Bluff opponents of Vogtle’s expansion. For starters, 20 percent of the plant’s jobs go to residents of Burke County, the other 80 percent to commuters from the Augusta-metro area, said George DeLoach, mayor of Waynesboro, the Burke County seat.

And many of the jobs associated with the reactors’ construction are temporary.

“It would remind you of when you watch a Western of how gold was discovered in the West,” Charles Utley said, describing Vogtle’s construction in the 1970s and 1980s. “I mean, it was big business at its best during construction. Everyone just knew it as a good place to have employment and get a job.”

As construction trailed off, though, jobs made an exodus out of the area, said Utley. “It’s just like the Gold Rush. It went to be a ghost town. The trailers left. The RVs left. The stores that were open to accommodate the workers, the restaurants all died. It went back to business as usual. Employment plunged back down because the jobs now were more professional.“

But DeLoach praises what Southern Nuclear and Plant Vogtle’s expansion could mean to a county that faces a 10.9 percent unemployment rate when the national average sits at 9.5 percent. The average median household income in Burke County is $33,000, about $20,000 less than the national average.

DeLoach said the plant makes up 70 percent of the county’s tax base.

“Burke County is receiving $25 million a year,” said DeLoach, who also runs a funeral home in Waynesboro. “(T)he $25 million comes in real handy to a rural county in this kind of economy. As the president of Georgia Power (Southern Nuclear’s parent company) stated, when these two—Units 3 and Units 4—are completed, he said you can just about double the taxes they are paying now. So that would be close to $50 or $60 million.”

With that money, DeLoach says the county sits ready and able to provide state-of-the-art technology and labs for the area schools. He adds that the plant has added to county infrastructure, too. The county had to expand emergency management services in case of an accident at Plant Vogtle, so now 12 substations create a greater county network.

The influx of Vogtle tax dollars had by no means spruced up Waynesboro or Burke County, though. Waynesboro’s main drag looks almost deserted, barren store fronts and blacked-out shadows of used-to-be commerce. In Shell Bluff, the community closest to the plant, some roads are still dirt and soft sand for stretches.

If there’s economic progress happening, the Shell Bluff residents feel cut out of it. “Not a whole lot,” Annie Laura Stephens said of the number of visible benefits she sees in her community. She was reared in Shell Bluff and continues to live there; Burke County High School is eight miles from the Shell Bluff community. “I mean you got the top-of-the-line high school in Burke County. Now see we’re out here in this community. We have to get to those schools.”

The Shell Bluff Country Store is one of two convenience stores within a 10 mile radius of Plant Vogtle in Burke County, Ga. Shell Bluff, technically part of the town of Waynesboro, is a rural neighborhood near the banks of the Savannah River, 10 miles outside of town. Photo by Lauren Frohne

OCCUPATIONAL HAZARD

The economic benefits are felt in any nuclear community. Hundreds of miles north of Vogtle, residents in Vernon, Vt., know the financial impact that Vermont Yankee has had.

For Michael Courtemanche, chairman of Vernon’s Selectboard, the plant’s effect transcends just money or jobs. He pointed out that the plant provides about 51 percent of the local tax base for the 2,200-resident community.

The plant employs 650 people, mostly all Vernon residents, and helps to stave off high national unemployment rates. Vernon’s rate averaged 5.1 percent in 2010, and surrounding Windham County enjoys a $46,546 median family income. Those jobs could eventually leave the community if the plant is decommissioned. And if those jobs go, Courtemanche said, other jobs will follow. And friends next. Then families. A nuclear domino reaction.

“My son’s friends are going to leave,” he said. “There’s going to be a number of houses on the market that will have a difficult time selling because now Vernon’s property taxes are going to go up because the plant won’t pay as much” once it is decommissioned and not part of the county’s tax base.

Deb Katz of Rowe, Mass., is less dramatic, but she is resolute in her belief that nuclear power plants have to become extinct. She organizes opposition from her home shadowed by a maze of birch, maple and pine trees high on a Massachusetts mountain.

Katz serves as the executive director of Citizens Awareness Network, a grassroots organization of 60 to 70 volunteers dedicated to eradicating the Northeast of nuclear power plants. She and her group were instrumental in the passage of Act 160 that gave Vermont the power to relicense Vermont Yankee—or not. In a fiery New York accent, she indicts companies like Entergy for buying off communities like Vernon, Vt.

“The struggle around Vernon is it’s an occupied town,” she said. “What corporations do is create an undermining of democracy by making their way into communities. ‘I’m the deacon at the local church. We do this volunteer work. We build playgrounds.’ …[But] when you go to wash your clothes at the local laundromat, you don’t know if you’re talking to a nuclear worker or not so that you’re really intimidated.”

Katz suggested that some of the workers would be kept on for decommissioning work. She noted that Vermont state Rep. Sarah Edwards introduced a resolution in the state legislature to create a training fund for the skilled work force that would be laid off.

Looking out at the activist landscape in the way a utilitarian general understands war, she intimated that she wants the plant closed at any cost. “I mean, no one’s guaranteed a job forever,” she says. “There are plant closings going on all the time, and I don’t feel responsible for that. It’s sad and it’s difficult.

“But that luggage shouldn’t be ours.”

THE NOT KNOWING

Chad Simmons, a Vermont activist with Citizens Awareness Network, had an epiphany as he ate his breakfast in downtown Brattleboro’s well-lit Elliot Street Cafe on a clear and sunny June morning. He is one part conformist, clean cut in his appearance, and one part resistor, blue nail polish painted on both thumbs.

Using words like “corporate skullduggery” to describe Entergy’s actions at Vermont Yankee, Simmons unequivocally approaches nuclear power with an almost anti-nuke soft-spoken whisper.

He said he never thought about nuclear power when he grew up in Wisconsin. It wasn’t until he headed to graduate school in Vermont in 2005 that nuclear became something he would face and eventually oppose along with different activist groups in the Brattleboro/Vernon area.

Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Plant resides on the Connecticut River in Vernon, Vt. In February 2010, a leak was discovered, and it was reported that the leaked tritium made it to the river. The leaks played a major role in the state legislature’s vote to close the plant as early as 2012. Photo by Lauren Frohne

He paused for a minute when talking about the Vernon community and how it accepts Vermont Yankee’s place there, despite all the risks activists cite. He put down his fork and pushed aside his plate, three-quarters of his vegetarian burrito uneaten.

It hit him that he doesn’t have everything figured out, that he struggles. The question of nuclear power doesn’t just come down to black-and-white side-taking.

And the answer that came to him was he might not have the answer to Vernon’s—or anyone’s—question about the benefits or risks of nuclear power.

“Who am I?” Simmons asked, either to himself or someone nearby. He takes a second to think about it. “It’s almost like it’s not our place.

“But it is our place. It’s our community, too.”

In that moment Simmons’ “a-ha” explodes quietly, like a mini-fission reaction. Just as he battles with finding answers to the issues surrounding nuclear energy, so do so many others. The complexity of the debate makes the struggle personal and clouds a clear vision of a nuclear renaissance.

Video quotes edited by LAUREN FROHNE

Camera and sound by LAUREN FROHNE and JESSEY DEARING